How to Evaluate the "Sustainability" of Sustainable Mutual Funds

Download a PDF:

Sustainable investing has come a long way. In its early days, investment managers, like Saturna Capital, created faith-based investment processes, focused on excluding companies or industries that conflicted with the tenets of an investor’s faith. This led to proactive investing, often referred to as advocacy investing, a process that encourages companies, sectors, and regions to engage in better business practices. Along with this, investment managers are now using positive screening to identify companies that not only engage in best business practices with their broad stakeholders, but also employ robust policies in the areas of the environment, social responsibility, and corporate governance (ESG).

Sustainable investing has gained immense traction in the broader investment community. Institutional asset managers have led the pack: in April 2019, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI) reported that institutional assets now exceed $86.3 trillion among its 2,372 signatories worldwide.1 In October 2018, The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Development (US SIF) Foundation's biennial Investing Trends report found that sustainable, responsible, and impact investing assets now account for $12.0 trillion—or one in four dollars—of the $46.6 trillion in total assets under professional management in the United States.2 This represents a 38% increase over 2016. The 2018 Trends report also found that “much of this growth is driven by asset managers, who now consider environmental, social, or corporate governance (ESG) criteria across $11.6 trillion in assets, up 44% from $8.1 trillion in 2016.”

Asset management companies have been quick to develop products to meet this growing demand. Additionally, new tools have been created to aid investment professionals in assessing a product’s sustainability. One tool is a globe rating system created by independent fund evaluation firm Morningstar. Globe ratings are part of a trademarked process that ranks a fund’s sustainability in its Morningstar-defined peer group, with five globes being the highest score, and one globe being the lowest. More recently, Morningstar has also developed a leaf rating system which identifies those funds that have the lowest carbon footprint in their peer group.

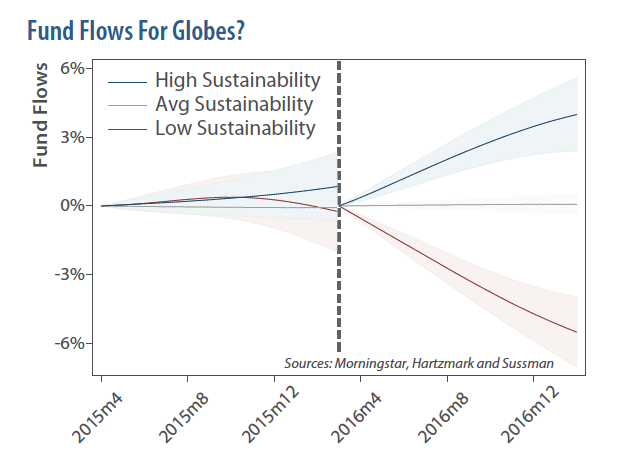

These sustainable ratings appear to influence investor behaviors. In their 2018 research paper Do Investors Value Sustainability? A Natural Experiment Examining Ranking and Fund Flows, authors Samuel M. Hartzmark and Abigail B. Sussman suggest that funds with top ranked sustainable attributes have seen investor inflows while more poorly ranked funds have experienced outflows.3 Their research finds that mutual fund investors collectively treat sustainability as a positive fund attribute, allocating more money to funds ranked with five globes and less money to funds with a one-globe rating.

According to the authors, the dashed vertical line indicates the initial publication of Morningstar’s sustainability ratings. To the left of the line, fund flows after controlling for monthly fixed effects are accumulated over the 11 months prior to the rating publication, and to the right of the line, flows are accumulated for the 11 months post publication. The blue line represents five-globe funds, the red line one-globe funds, and the gray line funds that are rated in the middle (two to four-globe funds). Prior to the rating publication, the funds were receiving similar levels of flows. After the publication, the funds rated highest in sustainability experienced substantial inflows of roughly 4% of their fund size over the next 11 months. On the other hand, funds rated lowest in sustainability experienced outflows of about 6% of their fund size. Over the 11 months after the sustainability ratings were published, the authors estimate between $12 and $22 billion dollars in assets left one-globe funds, and between $22 and $34 billion dollars in assets entered five-globe funds as a result of the globe rating.4

Overall, sustainable fund ranking seems to be influencing investor behavior; what isn’t clear, is how a sustainability focused fund is defined.

Morningstar’s sustainability ratings are an important development in the industry; however, they are still in the early stages of an evolving process. For example, when Morningstar initially created the globe ratings, the firm didn’t consider whether a fund’s prospectus intentionally included sustainable or responsible investing as an investment objective. The unintended byproduct of the initial globe rating was that some funds earned a higher sustainable ranking when sustainable investing was not an explicit consideration of its investment managers. Additionally, Morningstar initially determined a fund’s sustainability ranking using a specific point in time, rather than observing a fund’s holdings over a longer period of time. Arguably, this may have skewed its globe rankings.

Regardless, Morningstar certainly deserves credit for its efforts to educate investors on a complex and loosely self-claimed investment attribute among fund companies, managers, and their products. While there is still considerable room for improvement, Morningstar is responding to feedback. Overall, sustainable fund ranking seems to be influencing investor behavior; what isn’t clear, is how a sustainability focused fund is defined.

How to Evaluate a Sustainable Fund: A Primer

Uncovering the Basics

Reputable investment firms employ a transparent, explainable framework or philosophy to guide their investment process. If a firm claims to be using a responsible or sustainable investing framework, it is essential to understand how this framework is being applied. Investors can use the following list of questions to help explore how a fund company and its investment managers are integrating sustainability.

How is the fund or fund manager identifying themselves as sustainable?

While this may seem obvious, sustainability is an extremely broad and largely undefined investment term. Identify the focus of the investment process and the fund’s objective. Is the fund’s manager using an exclusionary, thematic, impact, or integrated framework? For example, a thematic framework might be a fund investing solely in alternative energy) while an integrated framework might include incorporating ESG attributes. Understanding how the fund defines itself is essential to understanding its objective. Check the fund’s website and read its literature, such as its prospectus or fact sheet.

Does the fund’s prospectus identify that the fund incorporates sustainability?

A prospectus is a legal document that gives investors clear guidance as to how the fund and the fund managers will manage the investment portfolio. If the sustainability information is offered in the marketing material, but not in the prospectus, then the fund is likely only aspiring to incorporate sustainability.

Does the fund offer a coinciding impact report that measures its sustainability integration?

An impact report measures the fund’s progress towards stated sustainability goals and explores in detail how the fund’s managers are incorporating sustainability. Published impact reports demonstrate accountability to shareowners and a commitment to transparency.

How does the fund manager or fund company define their sustainable investment process?

Does the fund manager offer examples of what is being included, as well as excluded?

This gives investors important context on how the investment manager may have decided to exclude particular securities in the past and/or why they opted to include others. Some fund companies offer case studies on their websites or as a part of their marketing materials. Have there been companies that a fund manager has chosen not to buy as a result of their ESG criteria screening, but would have potentially included under a non-sustainable lens?

To what extent does the fund manager use external sustainable resources, such as ESG analytical firms MSCI or Sustainalytics?

Investors should be cautious of any fund that exclusively uses an external vendor, as sustainable investment research is a holistic process with many conflicting points of view. In the broad definition of sustainability, even the “experts” disagree – and disagree a lot. For example, CSRHub, a data provider for the sustainability industry, found a low correlation (a weak relationship) between the ESG ratings provided by MSCI and Sustainalytics.5 Ratings discrepancies expose the differences embedded in their ratings frameworks and raises questions about overreliance on external vendors. In contrast, credit ratings assigned by S&P and Moody’s for companies and other borrowers are closely aligned.6

What’s in the fund’s portfolio?

This is very important and often overlooked. By simply reviewing the portfolio, you gain tremendous insight as to whether its underlying holdings align with its claims of sustainability. A portfolio should be reviewed holistically. A firm that invests for advocacy purposes, for example, is required to own securities of the issuer with which they are engaging in proxy work. Some funds, while identifying themselves as sustainable, may have large and diversified exposures in industries like hydrocarbon and mineral extraction, or other typically excluded industries. If the fund does own these positions, it is important to explore the fund managers’ rationale and how they are defining sustainability. Additionally, some fund managers approach sustainable investing as a momentum strategy – choosing to own once poorly rated sustainable companies if they have made considerable and meaningful strides. Further insight can be gleaned by talking to the fund company’s representative or the fund manager.

Mind the Details: Bond Funds

Historically, sustainable investing research has been more focused on equity investing than on fixed-income investing. For example, the UN PRI was launched in April of 2006 to build a collective framework among stakeholders to educate and incorporate best ESG practices. But it wasn’t until late 2014, eight years later, that the UN PRI began to apply responsible investing principles to the fixed-income asset class. This is a common trend, and, because of this, some of the sustainability scoring tools and research for fixed-income securities remain underdeveloped.

As such, the fixed-income sustainability tools offered by most vendors look at the issuer’s sustainable attributes, but not the attributes of the bond itself. This is an important distinction to make, since a qualified green bond, (a proceeds-use security specifically aimed at addressing key environmental objectives), or a sustainable bond (which has both environmental and social proceeds-use priorities), will most likely be overlooked. With the growing popularity of green bonds among fixed-income funds, this is a major oversight that has yet to be rectified. Be sure to ask if the fund has green or sustainable bonds in the portfolio, as these securities cannot be easily identified unless you have access to their security identification, such as their ISIN or CUSIP numbers, or the debt issuer’s prospectus.

Sovereign or sovereign-backed agency securities can present another unusual situation. There has been advancement in sovereign ESG work, with some ESG analytical firms offering relative rankings. However, understanding how the fund manager views sustainability among sovereign issues is very important. If a fund has a large holding in government-backed debt, say 25% or more, seek clarification of the fund manager’s intention. Is a large investment allocation a result of the fund manager taking action that is reflective of their view on the market, or do they have sustainable intentions? Beyond that, does the sovereign government’s sustainability standing in the world attach to the bonds it issues? In time, greater consideration of all of these factors will likely be incorporated in sustainable fixed-income reporting.

Broker & Advisory Platforms: What’s in the Sauce?

To gain market share and participate in the growing market for sustainable investment solutions, many large full-service brokerage firms, such as UBS Financial Services, Inc., and advisory platforms, such as Schwab, have begun to recommend sustainable funds and turnkey portfolios. As with sustainability rankings, investors need to know how these lists are compiled and what analytical framework is being used to formulate the recommendations.

Sustainability is very broadly defined, unlike tightly defined conventional investment categories familiar to industry professionals. Understanding how firms evaluate, prioritize, and rank sustainable attributes among a broad network of categories is key to determining whether a particular fund offering aligns with your priorities. While these platform providers may intend to aid your investment selection process, they could be making assumptions counter to your own, leading to unintended outcomes. Another thing to consider is whether the list of sustainable fund offerings consists solely of fund companies that “pay to play” – companies that pay a substantial fee to the platform in exchange for inclusion on the list. This is an important feature as these firms can act as gatekeepers as much as they offer a due diligence review.

Adding to the complexity, some platforms and brokerage firms employ outdated due diligence frameworks that do not offer a neat fit for the rapidly growing world of sustainable funds, in which many funds have yet to form an extensive history or accrue substantial assets. Occasionally, underperforming funds obtain a “financial makeover” when the fund company remarkets the fund as “sustainable” with a new fund management team. While there are several fund companies that have honorably held themselves to a sustainable standard with a multidecade investment track record, others have not. A newly minted, self-qualified sustainable fund with substantial assets under management warrants close review of the fund and the fund company’s history. Fund companies that do shift to a sustainably oriented investment process often need to go through a cultural shift, as adoption, integration, and implementation is a process rather than an event.

Conclusion

In typical Wall Street fashion, led by senior management’s fear of missing out on a major market development or fashionable trend, some investment companies have rushed to offer new sustainable products along with ambitious marketing activities. While this cynicism might be a bit extreme, the reality is that investors face difficult challenges in determining the authenticity and values alignment of sustainable funds and their providers, particularly in cases where sustainability is self-identified as well as self-qualified. The evolution of scores, globes, and peer group ranking by financial vendors can help investors navigate this process, but the lines are, at times, as fluid as the terms and definitions employed in the sustainable community.

The professional investment community’s progression toward the integration of broad responsible investment strategies reflects an evolutionary journey rather than an end point. However, this process has also revealed cases of flawed reliance on self-qualification. Until industry standards and terminology are further codified, investors should assume some responsibility in conducting their own assessments by verifying a fund’s sustainability objectives in its prospectus, examining the fund’s holdings, and researching the fund’s investment process, preferably via its impact report.

Sustainable funds and sustainable fund management will continue to develop as investors work to align their values and interests with their investments. Financial advisory professionals are well positioned to creating a competitive edge by helping investors map out their personal priorities and link them to highly customized solutions, deepening their relationships with their clients in the process. With a little extra review, investors can gain confidence that what they own truly aligns with the intentions they have for their portfolio.

Footnotes

1 UN PRI Principles for Responsible Investment Brochure 2019.

https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=6303

2 US SIF Report on US Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing Trends, The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, 2018, page 10.

3 Hartzmark, S. and Sussman, A. Do Investors Value Sustainability? A Natural Experiment Examining Ranking and Fund Flows, The Journal of Finance, January 15, 2018.

https://www.mccombs.utexas.edu/~/media/Files/MSB/Centers/HMTF/TFF/HartzmarkSussman.pdf

4 Wigglesworth, Robin. Rating Agencies Using Green Criteria Suffer From “Inherent Biases,” Financial Times, July 20, 2018.

https://www.ft.com/content/a5e02050-8ac6-11e8-bf9e-8771d5404543

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

Important Disclaimers and Disclosure

This material is for general information only and is not a research report or commentary on any investment products offered by Saturna Sdn Bhd. This material should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security in any jurisdiction where such an offer or solicitation would be illegal. To the extent that it includes references to securities, those references do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold such security, and the information may not be current. Accounts managed by Saturna Sdn Bhd may or may not hold the securities discussed in this material.

We do not provide tax, accounting, or legal advice to our clients, and all investors are advised to consult with their tax, accounting, or legal advisers regarding any potential investment. Investors should not assume that investments in the securities and/or sectors described were or will be profitable. This document is prepared based on information Saturna Sdn Bhd deems reliable; however, Saturna Sdn Bhd does not warrant the accuracy or completeness of the information. Investors should consult with a financial adviser prior to making an investment decision. The views and information discussed in this commentary are at a specific point in time, are subject to change, and may not reflect the views of the firm as a whole.

All material presented in this publication, unless specifically indicated otherwise, is under copyright to Saturna. No part of this publication may be altered in any way, copied, or distributed without the prior express written permission of Saturna.

About the Authors

Patrick Drum MBA, CFA®, CFP®

Senior Investment Analyst, Portfolio Manager, Amana Participation Fund, Saturna Sustainable Bond Fund